Populism and the fight for democracy.

Liberal democracy is facing its most perilous time since the rise of fascism a century ago. Between the GFC and now, their number has fallen by a third. Populist authoritarians thrive. What’s happening? And why?

Two visceral emotions drive the affairs of democratic societies: hope and fear. Of the two, the more potent is fear.

It’s what divides the two sides of political life. The method of progressive politics is to exploit the community’s need to feel hope; for conservatives, the way to power is to trade in fear.

Different times favour different sides. When we feel reasonably comfortable and optimistic, hope and its corollary, generosity, become possible. Right now, though, the times favour fear.

The world is waiting for the possible and perhaps likely return of Donald Trump to the US presidency.He is facing 91 criminal charges. His attorney general, chairman of the joint chiefs of staff, national security adviser and secretaries of both defence and state have proclaimed him unfit for office. The corporate world, traditional Republican supporters, is shying away and donations have plummeted.

But he is the unbackable favourite for the Republican nomination and according to the Real Clear Politics polling averages, Trump is beating Biden by three percentage points.

In western Europe, the Right is resurgent but, as in America, this new Right is different. There’s a scary savagery about them. In France, the far-right National Rally (formerly the National Front) is the most popular party. Its national leader, Marine Le Pen, has steadily risen in popularity and won 41.5% of the vote at the 2022 presidential election against Emanuel Macron. At the next election, in 2027, she could get there. A recent poll by the newspaper Le Monde found that for the first time, more French people believe that National Rally is capable of participating in government than not.

In the Netherlands, November’s election gave Geert Wilders’s far-right Party of Freedom by far the biggest vote: 23.6%, compared with 10.8% in 2021.In Poland, the centre-right Donald Tusk became Prime Minister, forming a coalition to defeat the far-right PiS incumbents. But PiS remains the biggest party in the Sejm (parliament).

In Germany, the far-right Alternative für Deutschland is polling at 22%, making it the second most popular party.

Italy is being run by a far-right coalition. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán remains secure in his “illiberal democracy”. Even the Nordic countries have elected right-wing governments. Narendra Modi is turning the world’s largest democracy at warp speed into the world’s largest former democracy.And so on.

Liberal democracy, having ended the twentieth century as the ascendant form of government, is now, in the third decade of the twenty-first, facing a perilous challenge that has not been seen since the rise of fascism in the 1920s. Whether it can survive, and it what form, remains unknown.

It would be foolish to assume any country is immune. That includes us.

Are we still democrats?

There is, of course, a difference between democracy and liberal democracy. Elections alone, even free and fair ones, do not guarantee how a government will behave in office. Liberal democracy provides far more stringent boundaries on power.

A liberal democracy follows a model first developed in the Enlightenment of the late 18th century. It demands the rule of law; separation of powers between the legislature, the courts and the executive; multiple political parties; an open society with freedom of movement; guarantees of basic human rights; private property; a market economy; and universal adult suffrage.

Most of the world’s 195 countries are not liberal democracies and never have been; even at the peak around 2010, only about 40 could be classified that way.

The phenomenon is almost entirely a product of the 20th century. There have been two booms and two busts. The first boom began after the first world war and ended with the rise of fascism; the second, much more substantial, boom after the second world war created the world we now know. But that boom too has ended; the number of confirmed liberal democracies has slumped by 36% from its peak around 2010. Some of those have become borderline liberal democracies; others have turned to authoritarian leaders.

That slump, often called the democratic recession, is marked also by countries outside this list becoming less democratic and less liberal. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has identified 27 countries that became less democratic in just seven years, from 2015 to 2022.

Since that report was compiled, some countries (Poland, Brazil) have improved but others (Argentina, Netherlands) have gone the other way.

A global report on the growing dissatisfaction with democracy by public policy analysts at the University of Cambridge found troubling results.

“Across the globe, democracy is in a state of malaise,” they wrote. “In the mid-1990s, a majority of citizens in countries for which we have time-series data – in North America, Latin America, Europe, Africa, the Middle East, Asia and Australasia – were satisfied with the performance of their democracies. Since then, the share of individuals who are ‘dissatisfied’ with democracy has risen by around +10% points, from 47.9 to 57.5%.

“This is the highest level of global dissatisfaction since the start of the series in 1995. After a large increase in civic dissatisfaction in the prior decade, 2019 represents the highest level of democratic discontent on record. While in the 1990s, around two-thirds of the citizens of Europe, North America, Northeast Asia and Australasia felt satisfied with democracy in their countries, today a majority feel dissatisfied …

“Citizens’ levels of dissatisfaction with democracy are largely responsive to objective circumstances and events – economic shocks, corruption scandals, and policy crises. These have an immediately observable effect upon average levels of civic dissatisfaction.”

If we don’t value it, we may lose it. As the song says: you don't know what you've got till it's gone.

Many surveys have tracked levels of support for democracy and have produced very similar results. By rebasing data to 100, this chart shows how attitudes to democracy in five nations changed in the first 20 years of the current century. The western nations are typical, though the United States is an outlier.

The series in the next chart cannot be compared with one another: they show relative trends, not absolutes. It does not mean that three times as many people in Hungary value democracy as in Canada or Australia. But it does mean that many more Hungarians want democratic reform after a long period of increasingly repressive rule.

Support for democracy is closely aligned to confidence in governments. Americans’ decline in trust of government has been happening for a long time, falling most sharply during the Vietnam war. It has never recovered.

Australia’s results are fortunately less discouraging. Although comparative data do not go back as far as in the US, the Australian Elections Study, which surveys voters at each federal election, shows that over 26 years nether measure has dropped below 50% and are both currently at 70%.

Despite these apparently optimistic results, right and far-right populist politics have been active throughout the period in Australia and still are.

John Howard, the most important Australian populist politician of the current era, gained and maintained his power by attacking “elites” – those who, like Paul Keating, advocated a republic, rectification of indigenous disadvantage, involvement with Asia and Asians, and major economic reform.Howard described himself as the most conservative leader the Liberal Party of Australia ever had. During his 33 years in federal politics, he shaped the party in his own image, much as Menzies had done a generation before. The Liberal Party under Peter Dutton is now a populist right-wing outfit akin to Le Pen’s National Rally, Wilders’s Party for Freedom and the Sweden Democrats.

What is populism and how does it work?

Broad swings to the left and to the right are not new. But this swing is characterised by the type of politician and by their methods. Seldom before have the techniques of meretricious populism been so pervasive or so successful.

But what is it? In the current context, it’s a political technique which seeks to characterise and demonise certain groups – the “elites” and other outsiders – as privileged, corrupt or threatening, and to sharply contrast these elites with the “neglected mass of common people” from whom the politicians wish to derive support.

Perhaps the most widely accepted definition comes from a paper published in 2012 in a political science journal, Government and Opposition:

“All manifestations of populism are based on the moral distinction between ‘the pure people’ and ‘the corrupt elite’. Whereas the former is depicted as a homogeneous and virtuous community, the latter is seen as a homogeneous but pathological entity.”

People and groups characterised as elite often are not very elite at all. Take, for example, targeting of the “black elite” during the Voice campaign and the even more frequent disparagement of “the inner-city elite”. And what about boat people?

Populism is a technique, not a philosophy. It’s a way of retailing fear. As such, it’s more readily utilised by the right than by the left: progressives cannot use fear-based hatred without abandoning who they are.

The number of parties classified as both right-wing and populist have multiplied, in Europe and elsewhere, to such an extent that they now represent a clear and serious threat to liberal democracy. Voter support is surging.

In the most recent elections the far-right won power in Italy, with the Brothers for Italy, the League and Forza Italia holding a combined 230 seats in the 400-member Chamber of Deputies. In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders’s Party for Freedom became the largest party in the House of Representatives with 37 seats.

In Germany, the Alternative for Germany won 10.3% of the vote in the 2021 federal election; it is polling most strongly in the states of former East Germany but is also doing well in the more prosperous west. In recent elections it won 14.6% in Bavaria and 18.4% in Hesse.

Populism and crisis

The populist technique works when the times suit it. A crisis, or at least the sense of one, seems to be an essential ingredient. The fear generated by a troubled time can be turned onto an outsider group to create a powerful and pervasive us-and-them mindset, blaming the privileged or dangerous outsiders and creating a sense of panic to which only the populist leaders have the solution.

In some hands, the technique can be used by authoritarian leaders to subvert an entire country and convert it from liberal democracy into an quasi-fascist personal fiefdom, initially through popular election and then by control of media, by voter suppression, by creating a system of crony capitalism comprising rewarding key supporters, and by discrediting or imprisoning opponents. Trump, Modi, Putin, Orbán, Erdoğan, Berlusconi, Netanyahu, Bolsonaro and Milei are some of the more recent examples.

The archetypical, though extreme, case was of course Adolf Hitler. He used the cascading crises facing the Weimar Republic in the 1920s and early 1930s: economic collapse, war reparations, strikes, and national humiliation after World War 1 – to blame Jews and communists. Finally, the Reichstag fire in 1933 heightened the sense of panic and grievance, and Hitler became chancellor.

In 1923, while he was locked up for insurrection, Hitler compiled a book of helpful hints for any other populists who might follow. “The art of leadership, he wrote in Mein Kampf, “consists in consolidating the attention of the people against a single adversary and taking care that nothing will split up that attention.”

“Populist leaders,” warned Jan-Werner Müller in The Guardian, “are not all nearly as incompetent and irresponsible as Trump and Bolsonaro’s handling of Covid would suggest. Their core characteristic is not that they criticise elites or are angry with the establishment. Rather, what distinguishes them is the claim that they, and only they, represent what they often refer to as the ‘real people’ or the ‘silent majority’.“At first sight, this might not sound particularly nefarious. And yet this claim has two consequences deeply damaging for democracy: rather obviously, populists assert that all other contenders for office are fundamentally illegitimate. This is never just a matter of disputes about policy, or even about values. Rather, populists allege that their rivals are simply corrupt, or ‘crooked’ characters. More insidiously, the suggestion that there exists a ‘real people’ implies that there are some who are not quite real – figures who just pretend to belong, who might undermine the polity in some form, or who are at best second-rate citizens.

“It is not true that masses of people are longing for strongmen and are turning away from democracy. But it has become easier to fake democracy. That is partly because defenders of democracy have not argued for its basic principles well, and partly because they keep underestimating their adversaries.”

Most seriously, defenders of democracy have been unable to counter the big, repeated lies that are essential components of the populist toolbox. “The broad mass of a nation,” wrote Hitler, “will more easily fall victim to a big lie than to a small one.”

And decades of research have confirmed what he and Joseph Goebbels understood intrinsically: “Repeat a lie often enough and people will eventually come to believe it.” Today’s research psychologists call it “the illusion of truth”.

An elite doesn’t have to be actually elite. A crisis doesn’t have to be real, though it helps if it is. The important thing is that the community must hold a pervasive belief that both are true.

What’s actually true isn’t the point. Facts need not matter: people who want to believe a big lie are impervious to truth.

If fear and resentment are essential selling-points of populism, it follows that the success of its techniques depend on the drivers of those emotions. Populism does not work on a population that feels generally content. It depends on social dislocation, declining standards of living, economic inequality and insecurity. It needs crises. Sometimes, but not usually, those can be manufactured. Real crises, and plenty of them, give opportunist populists the conditions they need to thrive and take charge.

Right now, they have a plethora of cascading crises, real and perceived, to work with: soaring inflation, insecure employment, falling real wages, inequality, climate change and natural disasters, mass migration, housing shortages, war and the fear of war.

Anxieties: inequality

When the wealth of a country is relatively evenly shared across its population, social cohesion can be expected to follow. When a large mass of people feel underprivileged and see another group getting away with the loot, the result is likely to be resentment, social fragmentation and a society ripe for populist demagogues.

The Gini coefficient is a broad measure of relative inequality. A figure of zero indicates complete equality, with everyone getting the same income. A figure of 1 means that one person gets everything.

But as the next chart shows, income inequality in western democracies does not correlate well with populist activity. Of these 16 nations, only the United States – the most unequal – and Italy have a major current problems with anti-democratic populism. Two of the other high-inequality states – Britain and Australia – do not. At least, they do not yet.

Conversely, nations where populism is strongest – Hungary, Poland, the Netherlands, Germany – are much more equal: at least, on this measure.

The distribution of inequality follows much the same pattern when we look at the proportion of income going to the top 10%, and to the bottom 50% of national populations. This looks like a poor predictor of vulnerability to populism.

It becomes somewhat clearer when we look instead at the very rich – the top 1%. Here, the United States is again at the top of the list. But the richest in Germany, Hungary and Poland have also secured exceptional levels of economic dominance. But even this measure is a poor predictor.

Perhaps the best explanation for the relative lack of influence that income inequality has on populist activity is that the very rich have both a clear interest in not being targeted as the elite they indeed are, and the means to ensure any blame is directed to others who have less power and less capacity to hit back.

A convincing explanation comes from Martin Wolf, chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, in a new book, The Crisis of Democratic Capitalism.

“How, after all,” he writes, referring to the US, “does a political party dedicated to the material interests of the top 0.1% of the income distribution win and hold power in a universal suffrage democracy?”

The answer is what Wolf calls “ pluto-populism”.

“This strategy has three elements. The first is to find intellectuals who argue that such policies [favouring the ultra-rich] will lead to a ‘trickle-down’ of wealth to the populace at large. Supply-side economics has been the way to argue this.

“The second element is to foment ethnic and cultural splits among the mass of the population and so, to take the most important example, encourage people to consider themselves ‘white’ or ‘anti-gay’ or ‘Christian’ first and members of the relatively disadvantaged second, third or not at all.

“The third element is to warp the electoral system through vote suppression, gerrymandering and, above all, elimination of restrictions on the use of money in politics.”

Anxieties: rich people feeling poor

You don’t have to be poor to feel poor.

Much depends on how a person’s income compares with those around them. If everyone else has more than you, you’ll feel poor. Almost no one in the countries listed in the following chart is, by developing-world standards, poor. It’s a matter of perception and comparison.

Broadly, these figures echo the charts on inequality: the US is worst – but this chart is a far better predictor of populist unrest. The nations experiencing some of the most rampant populism – the US, Italy, Spain, Greece and Turkey – also have high rates of relative poverty.

But this leaves the question of why some nations with fairly high poverty rates (Sweden, Australia) have fewer problems with populism while others (Hungary, the Netherlands, Poland) have much less. The answer, of course, is that many other factors are at work.

One of those is the way cost of living affects people who are not poor but who perceive that their living standards are slipping. Brazil, Hungary and Chile are among those in which inflation has taken the greatest toll on personal wealth. In most developed western economies, though, the sharp rise in inflation is a recent phenomenon, partly a result of supply-chain disruptions of the war in Ukraine and the China slowdown, and partly due to massive fiscal stimulus during the pandemic which was designed to keep firms in business and workers employed. All that money is now boosting demand at a time when supply is restricted. Inevitably, prices have risen.

Even these cases are not the worst. For that, consider Turkey.

Over the longer term, though, incomes in most countries have outpaced inflation. Only recently has that not been the case.

Data on disposable income is a way of showing, at least in the aggregate, how much people have to spend or save after taxes and inflation are taken into account. Generally, disposable income, and therefore living standards, have improved consistently across most western economies over the past 15 years, with the exception of Italy. There, the downturn was the result of the post-GFC rout in the southern member countries of the Eurozone (the PIGS – Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain) whose indebted economies needed currency devaluation which could not happen because they had unwisely given up monetary sovereignty to join the Euro.

In most countries, the recent economic downturn has been, by the measures of the past, mild. But its impact on perceptions has been anything but.

Consumer confidence is far more volatile than incomes data: there have been two major downturns in the past 15 years. But it’s hard to find justification for the recent slump in the aggregate data: but confidence is about perceptions, which often bear only a tangential relationship to reality.

The experience of a minority of people who are indeed experiencing a cost-of-living squeeze has come to shape the perceptions of entire nations. The failure of journalists and commentators to point out the difference between aggregate macroeconomic data, and the experience of a limited group, has produced this detachment from reality. “Doing it tough” is the cliché of the moment, and anyone who suggests the overall economy is actually doing quite well is derided.

Michele Bullock, the new governor of Australia’s Reserve Bank, found this when she spoke off-the-cuff to a forum in Hong Kong.“We have, like other countries, raised interest rates much more quickly than we have in the past and that has created in fact a lot of political noise and a lot of noise from the general public,” Ms Bullock told the conference.

“Despite that noise, households and businesses in Australia are actually in a pretty good position. Their balance sheets are pretty good,” she said.

“She said WHAT? Australia's Reserve Bank governor slammed for tone-deaf comments while on overseas trip,” roared the Daily Mail headline.

“The Reserve Bank chief has been slammed for telling an international conference frustration over interest rate hikes was just ‘noise’, it said. The story helpfully pointed out that “Michele Bullock … earns more than $1 million a year.”

She was, as a macroeconomist, speaking of the aggregate. Overall, that statement is true. It’s also a bit tin-eared, because nobody lives in the aggregate. We all have our own stories and, at the moment, people with mortgages, and many renters, are finding life difficult. For them, there is certainly a cost-of-living crisis. And constant reporting of these difficulties has led the entire country to believe the crisis is general. It’s not, but you can’t say that.

There’s a similar situation in most western countries. And that’s one of the problems with most of these figures: they don’t tell the whole story.

Anxieties: housing

People who own their own dwellings, or who can afford the costs imposed by rising interest rates and shortages of supply, are relatively unaffected by the current international housing “crisis”. For those on lower incomes, who rent or who are paying off large mortgages, it’s a different story. Again, it’s the second group, not the first, which is driving perceptions and, in turn, providing opportunities for populist mischief.

Interest rates, though not unduly high by historical

standards, are higher than they have been in recent years. The current

unusually sharp increase in rates follows an extraordinary period in which

rates fell to extraordinary depths and, in some cases, to below zero. People

who based their financial plans on such rates persisting have been,

unsurprisingly, pummelled.

There’s little enough in these data to justify the current international panic and sense of crisis. But the real experience of some, driving general perceptions, greatly assists, populist opportunists like Trump, Le Pen, Wilders and Dutton.

Housing affordability has declined in most western countries, with prices outstripping incomes. But when we look at trends over the past two decades, this does not represent an extraordinary peak. Canada is an exception, with affordability going from a low point (70 on the OECD index) in the first years of the present century to an unusually high level (140) now.

The recent worsening of affordability is undoubtedly significant for many and serious for some. But it does not help to explain why there is now so much more populist political activity now than there was 20 years ago.

Anxieties: climate and disasters

In a perverse way, the forces which have promoted climate denial, and which continue to derive huge profits from fossil fuels, are also likely to benefit from the generalised sense of anxiety and fear caused by climate-induced disasters.

An analysis of Google data commissioned by the BBC found that searches in English around “climate anxiety” in the first ten months of 2023 are 27 times higher than the same period in 2017. Searches have risen by 73 times in Portuguese, by eight-and-a-half times in Chinese and by a fifth in Arabic. Overall, Finland, Sweden, Denmark and Norway accounted for more than 40% of all “climate anxiety” searches.

This anxiety has been sharpened over 2023 by a series of climate-related disasters on all continents that indicate a tipping-point in the Earth’s liveability. But the concern is not new: it’s just that powerful forces in control of governments in apparently democratic states have prevented action being taken on the issues their populations demand.

A 2021 survey analysis published in The Lancet Planetary Health found deep levels of disappointment with the actions of governments across a variety of developed nations. Brazil, then under Bolsonaro, and Australia, then under Morrison, showed very high levels of disaffection. But even in Finland, twice as many people were unsatisfied as satisfied.

“Defence mechanisms against the anxiety provoked by climate change have been well documented,” the researchers wrote, “including dismissing, ignoring, disavowing, rationalising, and negating the experiences of others.

“These behaviours, when exhibited by adults and governments, could be seen as leading to a culture of uncare. Thus, climate anxiety in children and young people should not be seen as simply caused by ecological disaster, it is also correlated with more powerful others (in this case, governments) failing to act on the threats being faced.”

Those “powerful others” – and the term is not restricted to governments but applies even more to those with effective control over governments – will not go away. They will continue to seek, and often to succeed, in diverting blame from those who are responsible for our problems onto those who are not. For instance, onto immigrants.

Anxieties: immigration

Few issues provide such rich fodder for populists as unregulated migration. The fear of the outsider, the fear of being overrun by hordes of newcomers, and plain racism all play a part. Populists routinely play up legitimate concerns to create a perception of crisis, and then offer themselves as having the only solution.

Their simple, superficially plausible remedies are often brutal but seldom successful. As HL Mencken famously said: “For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple and wrong.”

That is not to say there’s nothing to worry about. Very high levels of immigration by people from a different culture, and who have often been traumatised by violence and repression, can cause social disruption. Generally, though, developed western countries have not had to deal with the large mass of displaced people.

More people worldwide are fleeing repression, war, dire poverty and starvation than at any time since the second world war. As climate change bites deeper, we can expect more and bigger waves of mass migration. Some of those will attempt to reach the rich countries of the west; relatively few will achieve that goal.

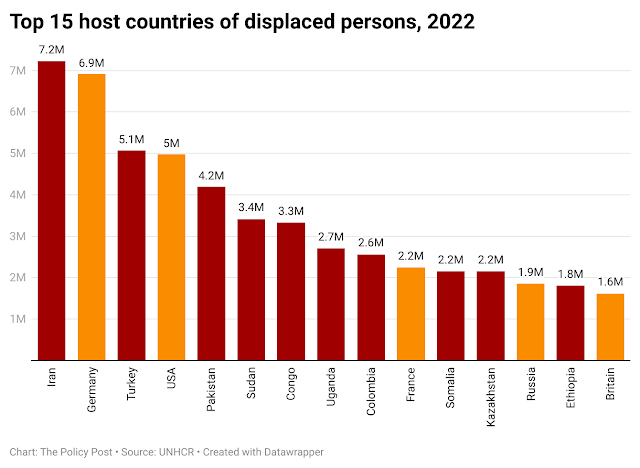

According to the UN refugee agency, a cumulative total of 108.4 million people have been forcibly displaced and remain in need of protection. Most – a cumulative 62.5 million – remain in their countries of origin as internally displaced persons. And in 2022, a peak year, over 10 million people tried to find places of safety outside their own countries.

The large majority remained within their regions or origin. Rich countries host just over a third of refugees and asylum seekers; the rest remain in nations that are poor or very poor, and much less able to cope with the influx.

Of the top 15 host nations, only five are wealthy, developed countries.

Of other western countries, Canada hosts 1,272,046; Sweden 1,230,666; Poland 1,130,352; Australia 1,021,683; Netherlands 938,094; Hungary 445,053; and Denmark 327,385.

But most displaced people either remain within their borders or flee to neighbouring countries. Seventy per cent are in nations bordering their home countries.

Migration has increased the proportion of foreign-born people in most western countries, but refugees and unregulated migration forms a small part of that. Australia, for instance, has one of the highest proportions of foreign-born people – but it always has, often as a result of deliberate government policy. In the first two decades of this century – from the millennium to the pandemic – the number of foreign students and skilled workers has largely been responsible. Refugees and asylum seekers have not. In Australia and elsewhere, the contribution of irregular arrivals to a country’s demographic composition ranges from minor to minuscule.

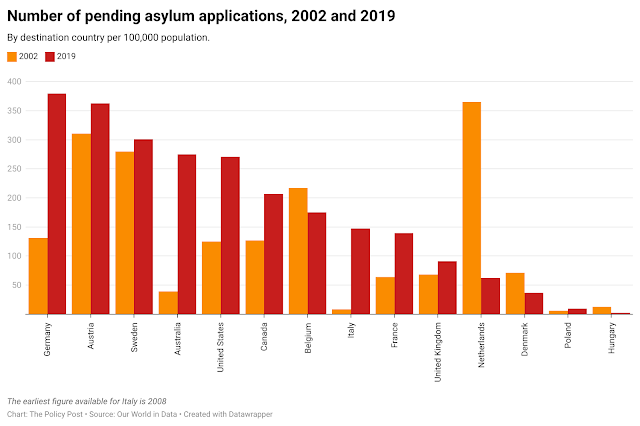

The data on asylum seeker applications bears this out. They have risen sharply in a few countries – Germany, Australia, Italy, France, the US – but nowhere have comprised more than 350 in every 100,000 population. That’s 0.35%.

There is no apparent correlation between the countries with policies to keep asylum seekers out and the actual numbers seeking protection. The countries in which populist politicians have made most noise – Britain, the Netherlands, Italy, Poland and Hungary – did not have a major problem two decades ago and still do not. In the Netherlands, Geert Wilders was elected on a platform of stopping asylum seekers. But the inflow, never enormous, had already stopped.

And Australia’s apparently large number of pending applications is almost entirely due to the policy of successive governments not to regularise the visa situation of asylum seekers who qualify as refugees, leaving them instead in permanent limbo and often in concentration-camp conditions in detention centres.

When populism works, and when it doesn’t: a case history

In Australia, two socially controversial questions were put to a national vote, six years apart. Together, they provide a natural experiment showing the conditions under which right-wing populism is effective, and when it’s not.

The first, about whether to allow same-sex couples to marry, was carried in a postal vote in late 2017 and became law soon after. The second, about whether to establish in the constitution a mechanism for consulting indigenous Australians about issues affecting them, was rejected.

Both polls were preceded by strong, well-funded campaigns for and against the proposals. In both instances, Liberal federal parliamentarians were split on the issue and the more conservative Nationals opposed. Labor and the Greens were in support, and took an active part in both Yes campaigns. The No campaigns were led by conservative members of the Liberal Party, most notably Tony Abbott and Peter Dutton. The most prominent figure in the Yes campaign was Penny Wong, leader of the Labor Party in the Senate.

The proposals had much in common. Both addressed historical disabilities of often-despised minorities. And in each, the Yes campaign appealed to the people’s generosity and the No campaign to their fear.

Both proposals, at the beginning, attracted strong community support. The same-sex proposal kept that support, despite a virulent crusade against it; the Voice proposal saw that initial support slip away, as a very similar fear campaign took hold.

It has been suggested that the main reason for the success of one proposal and the failure of the other is that voters were more likely to know people who were homosexual and much less likely to know indigenous people. That is true – and populists are most likely to be successful when the “elites” they disparage remain faceless abstractions rather than real people. But it is not the only, and probably not the main, reason.

The campaign against same-sex marriage pursued, throughout, the same range of arguments. In 2014, three years before the vote, these were failing to attract wide support.

Perhaps the most extreme moment came in 2012 when the far-right Liberal senator, Cory Bernardi, proclaimed in parliament that legalising marriage between people of the same sex would lead to polygamy and bestiality. “The next step, quite frankly, is having three people or four people that love each other being able to enter into a permanent union endorsed by society - or any other type of relationship,” he said.

“There are even some creepy people out there... [who] say it is OK to have consensual sexual relations between humans and animals.

“Will that be a future step? In the future will we say, ‘These two creatures love each other and maybe they should be able to be joined in a union’.

“I think that these things are the next step.”

It was too much even for Tony Abbott, the opposition leader. Bernardi’s outburst did nothing to help his cause or his career. Amid overwhelming public ridicule, he was forced to resign as Abbott’s parliamentary secretary.

But Abbott, soon to become Prime Minister, continued the fight with somewhat less dramatic language. When the political journalist Andrew Probyn described him as “the most destructive politician of his generation,” he was stating the obvious. Abbott was a warrior of the religious right and he dealt in fear; but he was clever, not crazy. And he was, by many orders of magnitude, more dangerous than Bernardi.The No campaign drew on two basic precepts of populist politics: fear of the unknown, and suspicion of elites: in this case, the elites were almost anyone who lived in the inner cities. And the campaign presented marriage as giving a divergent outsider group something they weren’t entitled to.

“I say to you, if you don’t like same-sex marriage, vote no,” Abbott said. “If you’re worried about religious freedom, and freedom of speech, vote no. If you don’t like political correctness, vote no – because voting no will help to stop political correctness in its tracks.”

“Thus,” wrote the veteran political journalist Michelle Grattan, “he tossed the battle around marriage equality into the centre of the culture wars.”

He was joined there by Scott Morrison, then Treasurer, and by Peter Dutton, then the immigration minister. Eric Abetz, the government’s leader in the Senate, called on Liberal front-benchers in support to resign their ministries. Christopher Pyne, leader of the house and a supporter, described the comments as “unhelpful”. Malcolm Turnbull, another supporter who was soon to become Prime Minister, presumably felt the same.

|

| Dutton ... fought marriage equality |

“It is unacceptable that people have used companies, and shareholders money, to try to throw their weight around in these debates,” he told a Liberal National Party conference in Queensland, to loud applause.

“And certainly don’t use an iconic brand and the might of a multi-billion dollar business on issues best left to the judgment of issues and elected decision makers.”

The conservative parties remained solidly, though not exclusively, opposed.

But those numbers would not have been enough to successfully defeat a parliamentary vote. Dutton, faced with that reality, threw in a distraction. He advocated a “plebiscite” of the population to decide the issue. It was both a delaying tactic that would allow a formal, determined No campaign to take place.

And so it happened. But the No campaigners did not prevail. Their messages of fear were outplayed by the messages of hope and generosity from the other side. Finally, towards the end of 2017, the results came in. The support of around 60% revealed in early polling held firm.

The postal vote was not compulsory but 79.5% of eligible Australians took part. The measure was carried in all states and territories and in 133 of the 150 federal electorates. In Tony Abbott’s electorate of Warringah in Sydney, support was 80.8%; in Peter Dutton’s seat, Dickson in Brisbane, it was 65.2%. In Tasmania, Eric Abetz’s home state, it was 63.6%.

David Flint, a gay retired academic who had led the campaign against the republic referendum in 1999, had recited the same populist tropes he’d used back then, and would use again against the indigenous Voice to Parliament. Just as Donald Trump refused to accept the results of a free and fair election, David Flint refused to accept the postal plebiscite result. When told that nearly 80 per cent of voters had returned their forms, he asked, “How many of them are genuine?”“What’s happened is because the politicians have created this mess, it’s allowed the Marxists to move in and replace education with propaganda.”

“They want to undermine the family, that’s part of the agenda of the left, and to do this what they’ve decided is that they’ll create a completely non-existent LGBTIQXYZ community. There is no such community.”

Flint, fortunately, is no Trump. When the bill was introduced in the Senate, the crucial motion passed by 43 to 12. Among those opposed were Eric Abetz, Cory Bernardi, and a sole Labor senator, Helen Polley.

In House of Representatives, the bill passed into law with only four votes against: Liberal Russell Broadbent, Nationals David Littleproud and Keith Pitt, and independent Bob Katter. Abbott and Morrison abstained. Dutton voted in favour.

Fear had been defeated. Generosity had won.

When Anthony Albanese made his victory speech in May 2022, and promised to introduce a referendum on the indigenous Voice to Parliament, it was widely believed that this, too, would be supported by the Australian people.“Together we can be a self-reliant, resilient nation, confident in our values and in our place in the world,” he said. “And together we can embrace the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

“We can answer its patient, gracious call for a voice enshrined in our constitution. Because all of us ought to be proud that amongst our great multicultural society we count the oldest living continuous culture in the world.”

Community support for the measure was overwhelming; at 65%, it was even higher than for same-sex marriage at a similar stage. That support remained solid until the middle of 2023, when the wording of the referendum question was announced and its opponents began their campaign in earnest.

There was a lot at stake, not only for aboriginal and Torres Strait islander people. Albanese’s desire to take party politics out of the matter was quickly thwarted by Dutton, who became the de facto leader of the No campaign.

That campaign followed the classic populist playbook: fear of the unknown, and jealousy of elites.

Within that framework, there were two principal components: demands for ever more detail that could never be satisfied because the parliament would later provide those details in the normal way; jealousy and disdain of allegedly privileged, powerful elites; and the fear that some people (indigenous people) were getting something they weren’t entitled to.

David Flint, reliably, made his contribution. Amazingly, he accused the Liberal Party under Peter Dutton as being insufficiently conservative.

“So our two major parties are competing to satisfy the inner-city elites to which most politicians belong,” Flint wrote.

Australia’s electoral system was, he said, “a system more open to fraud than most.”

“Just what point is there in Labor and the Liberals suiciding, throwing themselves at the feet of the fickle and foolish inner-city elites?”

This time, though, he accepted the result he liked.

Flint’s opinion piece, in The Spectator Australia, identified a key theme in right-wing populism. It was headed “The elites versus the Aussies: We are now two nations.”

It is no coincidence that when Pauline Hanson founded her party in the late 1990s, largely on the premise that aboriginal people were getting too much, she called it One Nation. There are people who are part of a nation – the virtuous people – and those who are beyond the pale and who must be loathed and excluded.

The referendum carried in only one of the six states and two territories.

In the conservative Australian Financial Review, senior journalist Aaron Patrick celebrated, railing against the major companies that had supported the referendum.

“The failure of the Voice represented a backlash against elite influence.” He wrote. "Voters’ anti-elitism isn’t an Australian phenomenon. In the US, Donald Trump continues to be regarded as a formidable contender for the presidency, despite the four criminal charges against him.

“In Australia, the Voice would have created a new, black elite, which may explain why white elites were so supportive; it is a model of power they understand.”

There was, of course, no acknowledgement that almost all that newspaper's readers, and certainly all financial journalists, live in the inner cities and unquestionably form a particularly rich and powerful elite. But hypocrisy is an essential tool of the successful populist.

It is, of course, extraordinary that a referendum could be defeated, at least in part, because it was thought aboriginal people were getting something the rest of us don’t have. One statistic alone ought to rebut that utterly: the gap in life expectancy.

Australians had to be given a reason to absolve their consciences from concern that they were making a decision that was clearly racist. A few aboriginal people were pleased to provide that assurance. The most prominent was Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, a National Party senator from the Northern Territory. When Julian Leeser, the Liberals’ indigenous affairs spokesman, resigned from the front bench because he supported the Voice, Dutton replaced him with the newly elected far-right Price. She was the deciding factor in the outcome.

During the campaign, Price made constant headlines with statements that would, in other circumstances, remove her from serious consideration. In the context of an inflammatory controversy with race at its centre, those statements worked.Colonisation had no adverse results on aboriginal people, she said. The Australian Electoral Commission was allowing indigenous communities to be manipulated into supporting the Voice. The gap in life expectancy was not about race but about place: aboriginal people living in remote areas were no more disadvantaged than white people in the same areas. It is perhaps not surprising that she rejected 52 interview requests from the ABC.

She demonstrated how lies, in the hands of a clever populist, can be laundered and rendered into a simulacrum of truth. According to one poll, she is now either the second most-trusted political figure in the country. Another poll rates her as the third most likeable.

Price made racism respectable. The cost of that to the country is incalculable.

In 2017, 138 federal electorates returned a majority “yes” vote for same-sex marriage and only five against. Six years later, the situation was almost completely reversed: 121 electorates voted against the Voice and 29 in favour.

The Voice issue destroyed, at least for a time, the Albanese government’s ascendancy. Labor’s primary support fell from 38% before the campaign to 31% after.

By late 2023, even after preferences, the coalition was level with the government. From Dutton’s point of view, that was the whole point of the exercise. It is fanciful to think this was about deciding the best was of making policy on aboriginal affairs. It was naked, nasty politics.

The populists lost the first time but won the second. They won not because they had changed, or that the issues were so dissimilar, but because the country had changed.

The foundations of that change can be seen in the increasing sense of despondency about both the national economy and about people’s own financial security. For almost 20 years the Lowy Institute has run a regular poll asking the same questions. The answers about the nation’s economic performance track a national mood.

During the Global Financial Crisis, Australia was one of only two developed nations to avoid recession. There were two main factors – China’s demand for minerals and the Labor government’s injection of major stimulus into the economy. Australians felt the effects of the crisis, just as everyone else did. But we felt good about ourselves.

By 2017, when the same-sex marriage campaign occurred, economic optimism was at a high point. But in 2023, in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, the nation’s first recession in 29 years, soaring inflation, interest rate increases and a housing crisis, the mood changed. We remain more optimistic than pessimistic but it is an unsettling time.

As the costs of housing climbed, so did the difficulties of people trying to enter the property market or to service a mortgage.

As these CoreLogic figures show, newly-signed rental agreements have also risen sharply, particularly for units in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane.

But at the same time, the income needed to pay these bills have gone backwards. In just 12 months, average disposable incomes in Australia fell by 5.1%.

The cost-of-living squeeze is unevenly spread: renters and owner-occupiers with large mortgages are bearing a disproportionate impact of rising prices and falling incomes. But the mood of the whole nation has been affected. When so many people feel threatened and the level of communal worry surges, the politics of fear will succeed and the politics of hope and generosity will fail. Peter Dutton knew that; Anthony Albanese apparently did not.

The decline in the Labor government’s fortunes, tied so closely to the Voice referendum, are likely to rebound as it recedes into the past. As inflation subsides, and interest rates start to come down, the zenith of destructive, opportunistic populism can also be expected to pass. It may be, though, a long time before the nation again feels optimistic and generous; until then, the fight for liberal democracy, a nation in which everyone has a place, will be tough. Its success is not guaranteed.

What’s at stake?

The fight against populist erosion of liberal democracy may just be beginning. The importance of the outcome cannot be overstated, because upon it depend not only the individual rights and freedoms of citizens but the entire mechanism, economic as well as political and legal, that drives western culture.

It is not a coincidence that the most prosperous countries in the world are liberal democracies with market economies. As Martin Wolf and others have pointed out, the two go together. Damage one, and you risk both.

Until well into the 19th century democracy, let alone liberal democracy, did not exist. The United States had elections and a constitution by 1789 but it also had an economy based significantly on slavery. Women were denied the vote and an equal place in politics, society and economic life. Twelve US presidents were slave-owners; even Woodrow Wilson was born in a slave-owning household.

The long, slow road to democracy followed the development of an industrial capitalist economy, but three paces behind. They evolved together, as two aspects of the same design. As political participation of the broad mass of national populations increased, economic power shifted. The extremes of early capitalism, in which almost all the benefits went to the owners of capital and the owners of labour were reduced to meagre subsistence, were eroded. The countervailing power of union membership and political representation met the power of the bosses and, in the ensuing struggle, found a generally workable equilibrium.

That fragile equilibrium underpins the modern developed world. Upsetting the balance of interests will predictably disrupt, and perhaps destroy, the capacity of moderate political democracy and a tamed capitalism to deliver the freedoms and wealth we now take for granted.

The political structure is responsible for providing the framework under which economic activity takes place. It sets the boundaries: safeguarding competition, setting and enforcing the rules of finance and trade, and rectifying market failures.

If plutocratic interests take hold of the polity, the balance is lost. Adam Smith, back in 1776, wrote that “people of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices …

“The interest of the dealers, however, in any particular branch of trade or manufactures, is always in some respects different from, and even opposite to, that of the public. To widen the market and to narrow the competition, is always the interest of the dealers.”

The neoliberal era from which the world is now emerging demonstrated the folly of giving too much power to big capital. The privatisation experiments of Thatcher in Britain and Kennett in Victoria failed to deliver the promised benefits but, instead, left a legacy of inefficiency and corruption that will take decades to unravel. As examples, take the sell-off of Britain’s water and sewerage assets, ambulances and hospitals in Victoria, and the frenzy of privately-built toll roads that have put large parts of the nation’s highways network into the hands of one company.

But the market must have enough freedom, within necessary bounds, to function efficiently. One of the great, painful lessons of the 20th century is that socialism – the public ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange – does not work. It is not possible for those in control of a command economy to detect every tiny element of activity. Inefficiency is built in. And, without exception, the attempts to establish pure socialism – communism – led not to the dictatorship of the proletariat but only to dictatorship and finally to economic and social collapse.

Since Deng Xiaoping’s reforms from the late 1970s, China has seemed to be the exception in which a highly repressive political system, strict control of information and ideas and a personality-cult leadership presided over a period of extraordinary economic growth that led unprecedented numbers of people out of extreme poverty and some of them into considerable prosperity.

But this is a work in progress. The mistakes of past administrations and the injudicious authoritarian diktats of Xi Jinping have created a serious economic predicament that could turn out to be terminal either for Xi or for the Communist Party. Even if both survive, China’s march to riches may not. Few newly developing countries have avoided the middle-income trap. Their early advantages, mostly cheap labour, evaporate when wages rise and start to price manufactured exports out of world markets. But without a consumer economy, a highly-educated population and a sophisticated intellectual society, the leap to a full developed status remains elusive.

If China’s development stalls, the implicit contract between the Communist Party and the people – accept repression in exchange for ever-increasing prosperity – would create impossible pressures. The result of serious internal conflict would be calamitous for China and devastating for the world.

In many countries – the United States, India, Israel, Hungary, Poland and others – the threat of extreme authoritarian populism is either an immediate threat or an accomplished reality. Other western countries, including Britain and Australia, are not as close to the crunch-point. But it would be naïve and foolish to assume they never will be.

Neither Boris Johnson nor Peter Dutton could create successful authoritarian regimes. Johnson lacks the discipline and Dutton lacks the charisma. But if circumstances change enough, a new, apparently benign leader could emerge, and probably would.

It would take a confluence of disasters – a severe and prolonged economic downturn, high and intractable unemployment, climate-induced natural disasters – together with incumbent political leaders who were seen to be incompetent or uncaring. The chances of such a confluence developing over the next two or three decades are considerable.

In her last book, Fascism: A Warning, Madeleine Albright recalled a conversation with her political science students:

“I put the question to my class of graduate students at Georgetown: ‘Can a fascist movement establish a significant foothold in the United States?’ Immediately, one young man responded. ‘Yes, it can. Why? Because we’re so sure it can’t’.”

.jpg)