Shocks and aftershocks

4: And then the world ended.

As the 19th century progressed, reforms were minor and grudging, doing little for the great mass of the people. Finally, in 1914, the edifice collapsed.

|

| Cheap labour fed the profit motive |

The intensely complex events leading to the outbreak of war

in August 1914 formed some of the most exhaustively studies periods in the

whole field of historical scholarship. The basics are well-known: a web of

international treaties, military and economic rivalries, nationalist yearnings

and a bullet fired in Sarajevo.

But the origins of that turmoil go back much further, to a

world which was moving fast, a political and social system that no longer

functioned, and a European power elite that was arrogant, entrenched, inept and

utterly out of touch.

In the century between the end of the Napoleonic Wars and

the beginning of the First World War, the government of Britain was divided

almost equally between Whig-Liberals and Tory-Conservatives. As the century

progressed, the philosophical tenets of liberalism were adopted by both sides,

with differences in emphasis more than in substance.

Broadly, the established colonies in Canada, Australia and

New Zealand regarded themselves as British and adhered to British policy. Far

away from the rigidities of English society and politics, a more egalitarian

culture had developed. Liberalism dominated, with a new flavour: more

fair-mindedness, less respectful towards established power. Extension of the

franchise, the secret ballot and votes for women were established much earlier

than in Britain.

Between 1860 and 1914, the railway boom transformed not only

the economies of industrialised nations but also their societies and politics.

In that time, railway lines in Britain more than doubled and, in the US,

increased more than eightfold. In Australia, over 2,000 kilometres of track had

been laid by the time of federation in 1901. Steam replaced bullock-drays and

mule-trains. New towns and cities appeared, then grew.

As industrial production grew, so did overall economic

growth. GDP per capita rose in bursts, separated by frequent recessions. The

most innovative and dynamic economies – the US, Britain, Australia and Canada –

did best. Outputs of industry and agriculture both rose spectacularly but the

US had the advantage of both. Russia and Italy lagged, and even Germany failed

to benefit adequately from the new economic paradigm.

But boom-and-bust cycles disrupted national and

international economies throughout the 19th century. It was an

inevitable result of liberal orthodoxy: that government should keep out of the

way and let free, largely uncontrolled markets get on with the job of creating

wealth.

The increased wealth went disproportionately to those who

were already wealthy. In Britain, the share going to the top 10% increased and

the share going to both the bottom 50% and to the growing middle 40% fell.

In the US, inequality in the period was somewhat less

severe, though only in the top half of society. The bottom half benefited from

overall growth but their share of total income only achieved British levels at

the end of the century. These figures mean that the middle 40% of Americans –

those who were reasonably comfortable but by no means rich – were better off

than their counterparts in Britain.

Everywhere, though, the relative position of the lowest

echelons remained dire. The share of the population of the leading European

countries who were living below the level of subsistence fell only slowly.

Economic growth from industrialisation helped

but as incomes grew, so did prices. And because populations were growing

quickly, the total numbers of people living below subsistence level almost

certainly increased.

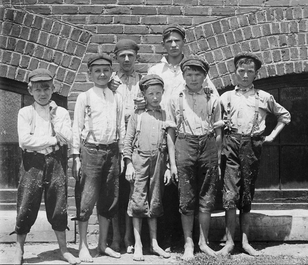

A proxy for the way nations treated their most vulnerable

citizens can be found in the statistics for child labour. The proportions of

British children aged 10 to 14 who were working fell between 1860 and 1914 but

remained high even then.

But the load was not evenly spread. Child labour was

concentrated in the industrial North. In 1892 Lancashire had 93,969 children

working half-time. Yorkshire had just under 45,000 and Cheshire almost 10,000.

From the 1880s, campaigners tried to end the system grew but

were opposed by employers and by the unions. At a time when adult wages were

below subsistence level, the income from children’s labour could make a

difference between eating and starving.

In Italy, it was far worse and took even longer to end. By

the outbreak of the First World War, half of all boys and over a third of girls

were working.

Despite massive improvements in public health between 1860

and 1914, rates of child mortality in Britain and France barely changed.

Australia and New Zealand were much healthier places for children, even though

one child in 10 still died before their fifth birthday.

Something more might have been done about the bitter class

divide if effective democratic processes had been in place. They were not.

There was a good deal of pretence. In Britain, the Reform

Act of 1897 doubled the franchise – from 5% of the population to 10%. Throughout

the century, prime ministers and foreign secretaries sat in the unelected House

of Lords and never had to face voters themselves.

In Italy, the electorate was quadrupled in 1882, to 7% of

the population. Until 1893, the vote was restricted to under 3%, and then went

to 22%, but half got two or three votes.

In France under the Third Republic (1870 to 1940) the

National Assembly was elected by universal manhood suffrage but that disguises

the impact of the violent repression which defeated the Paris Commune of 1871

and effectively obliterated independent working-class politics and socialism.

In Germany, Bismarck held all ministries personally,

appointing delegates to do the work.

“Our epoch, the epoch of the bourgeoisie, possesses,

however, this distinct feature: it has simplified class antagonisms,” said the

Communist Manifesto. “Society as a whole is more and more splitting up into two

great hostile camps, into two great classes directly facing each other – bourgeoisie

and proletariat.”

Against this disenchanting background, the working-class

political movements in Europe, with no experience in politics or government,

became more angry, violent and riven by factions. The two main elements were

Marxists and Anarchists.

|

| Karl Marx as a young activist |

The Anarchists believed that if they assassinated enough

kings and politicians, they could dispense with stages one and two, and move

straight to bliss.

As Utopian visions tend to, the vision of the workers’

paradise led instead to demagogy, tyranny and slaughter. But that was to come.

Socialist economic policy – the collective ownership of the

means of production, distribution and exchange – had a longer life. But, as

events in the following century unfolded, it would fail also.

In Britain, the character of the people and politics did not

fit with the extremist positions of socialists in continental Europe. There, a

much more moderate move towards workers’ rights and the nationalisation of

industry eventually mutated into the Labour Party. But class warfare continued

to fracture politics, society and the economy.

Meanwhile, the increasingly embattled existing leaders held

on for the moment, partly by giving some ground to the socialists. An example

was Bismarck’s initiative of the first social welfare policy, giving support to

the sick and unemployed.

As they resisted an impending, unpredictable and potentially

destructive transition, the ruling interests sought distractions. There were

two: other people and other nations that could be characterised as the enemy;

and the glory of colonial expansion.

In the 24 years between 1880 and 1914, the number of

colonies held by European powers almost tripled. At the outbreak of war,

Britain had 54, France 21 and Germany 12. Almost all the new possessions were

in Africa.

Imperialism had no sound economic basis. Historical research

has shown clearly that the empires cost far more than they earned. The imperial

nations lost a great deal of money but fortunes were made by some individuals.

The historian A J P Taylor wrote: “In almost every case, European countries

spent a great deal of money in acquiring colonies which proved to be of little

economic value.”

It is a fallacy, Taylor argued, that “policies were

conducted for the benefit of all, much as companies are conducted for the

benefit of the shareholders. This was not so … The humble investor might lose

his money but the mighty company promoter did not go away empty-handed even if

the company he promoted went bankrupt.”

If that money had instead been spent more wisely and for the

good of the people, the conditions of the bottom three-quarters of society

would have been a great deal better and the upheavals which led to war and

revolutions might have been avoided.

In all the major European countries, fear and hatred of

outsiders was weaponised by politicians and the press for the benefit of those

with power. As early as 1877, a scare about Russia produced a music-hall

song which served as a kind of anthem for the mood of the times.

We don't want to fight but by

Jingo if we do

We've got the ships, we've got

the men, we've got the money too.

That dogs-of-war craving for blood

and glory characterised Europe for 30 years before war broke out. It powered an

arms race between Britain and Germany. Each toiled to manufacture more guns and

build more big battleships. There could only be one outcome.

The economic and political liberalism which, in various

forms, had prevailed throughout the century was doomed by the blindness, hubris

and stupidity of those clinging, with ever-diminishing legitimacy, to power.

Their folly and rigidity led the nations of Europe, each trying to secure its

own security, to create a network of alliances which ensured any local conflict

would result in general war. Francis Joseph, the old and reactionary emperor

who had been in power since 1948, thought war with Serbia would remain local.

He was wrong.

NEXT: 5: After Armageddon, rebirth. Socialism turned out to be much worse than liberalism. Then a new way appeared ... for a while.