Shocks and aftershocks

6: Peace, love and company profits

The upheavals of 1968 presaged the ultimate triumph of liberalism. Personal freedoms were finally realised – but neoliberal economics failed just as badly as ever.

On 29 April 1968, two weeks and two days after Martin Luther

King was murdered, a new musical, Hair, opened on Broadway:

When the moon is in the Seventh

House

And Jupiter aligns with Mars

Then peace will guide the planets

And love will steer the stars:

This is the dawning of the Age of Aquarius.

|

| Hair: a global smash hit |

Hair made a great deal of money for its Wall Street

investors but the hippie movement, which inspired it, was a sham: silly and

vague to the point of imbecility. It was a kind of informal communism: what’s

mine is yours and what’s yours is mine. In practice, it tended to default to

the second rather than the first.

The hippies thought they could change the way the world

functioned but had no notion of how to handle the production, distribution and

exchange of the goods and services upon which they, like everyone else,

depended.

It didn’t last long. The headquarters of the hippie movement

– the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco – dissolved in destitution and

disenchantment when the drug dealers moved in. A new era had genuinely begun,

but this was not it.

As it turned out, the western world was not embarking on a

new paradigm but returning to an old one. The economic elements of liberalism

had mutated somewhat since the time of Adam Smith and Jeremy Bentham,

recognising the need for governments to set the basic rules without which

modern finance and trade would be impossible. But previous iterations had

largely ignored the other principal element of the liberal agenda: individual

rights and self-realisation.

The new movements for personal liberation emanating from the

American civil rights crusade – on feminism, gay rights and racism – were

entirely consistent with the original concepts. Bentham, for instance,

supported equal rights for women, the right to divorce, decriminalising homosexuality, and the abolition

of slavery, capital punishment, and physical punishment, including

that of children.

It was in social policy, rather than economic policy, that

the new era produced major change. The democratic world is now vastly more

socially liberal and tolerant of difference than any culture in the whole of

recorded history.

But the generosity and fairness did not extend into economic

policy. As it turned out, neoliberalism was not all that much different from

paleoliberalism.

A series of economic shocks in the 1970s, complicated by the

ineptitude of government responses, ended the post-liberal period. Stagflation

– weak or negative growth with high inflation and high unemployment – was not,

according to the models, supposed to happen.

Keynesian demand-side policies were blamed and the world

returned to a revivalist liberalism: small government, austerity, trickle-down

economics, privatisation, anti-union legislation and deregulation of the

finance sector. The prophets of the new era were Ronald Reagan in the US and

Margaret Thatcher in Britain.

“It’s Morning in America” ran the Republican slogan for

Reagan’s re-election in 1984. It was, too, for some.

For the fifty years following the end of the postwar

Keynesian period, overall economic growth continued at about the same rate. The

return to hard-nosed liberalism did not produce stronger growth than the

welfare state that preceded it.

The change was not in overall wealth creation but in who

benefited from that new wealth. Those at the bottom and middle of the income

ladder fell backwards; those at the top got the loot.

The United States, where neoliberalism was most rigorously

applied, is the most egregious example. As the new century began, the share of

income going to the top 10% surpassed that going to the middle 40%. The bottom

half of society fell drastically, from 21% in 1968 to 14% in 2007. That’s a

relative fall of 30%.

The trend towards greater inequality was unaffected by which

side of politics was in power. Britain’s social ethos made Margaret Thatcher’s

agenda somewhat less easy to implement than Reagan’s in America, but the pattern

was repeated there too.

Australia began and ended the period with a more equal society than in Britain or the US. Here, industrial laws and the less-savage implementation of neoliberal reform by the Labor government of Hawke-Keating softened the impact. Nevertheless, the middle class went backwards and the top echelon did very well.

Again, the trend continued despite changes in government.

The neoliberal period produced a decline in the quality of

public services and an increase in their costs. The return to a free-market,

small-government ideology was almost universal, though applied in some

countries with less rigour and more humanity than in others.

The 1970s saw the collapse of the (semi)-Keynesian

settlement of the previous 30 years, and the war in Vietnam had a good deal to

do with it. The US Department of Defence calculated that military costs alone

between 1965 and 1974 amounted to $US139 billion. In today’s money, that’s $1.1

trillion in US dollars and $1.7 trillion in Australian dollars.

“The war cost 10 times more than support for all levels of

education and 50 times more than was spent for housing and community

development during that same period,” Clayton said. “The United States spent

more money on Vietnam in 10 years than it spent during the nation's entire

history for public higher education or for police protection.”

In 1971 the cost of the war had become so great that America

no longer had enough money to maintain the parity of its currency with gold. A

balance of payments crisis meant that the US no longer had enough gold to cover

its currency, and not enough spare cash to buy more gold. Richard Nixon first

suspended the Bretton Woods system, then cancelled it altogether. Nations

around the world often still pegged their currencies to the US dollar but could

change that level as they wished or simply float, as Australia’s dollar has

since 1983. Nevertheless, the US dollar was still the most significant and

safest in the world, so a fiat currency (America’s) replaced gold as a prime

guarantor of value.

With national currencies no longer fixed, the two Bretton

Woods institutions – the IMF and the World Bank – had a problem: they no longer

had anything to do. But huge international bureaucracies, with so many careers

and special interests involved, do not suddenly disappear for such a paltry

reason as no longer having a reason for existence. So they found a reason.

The IMF and the World Bank went on providing loans but had a

new mission: to enforce Washington’s hardline policies on fiscal rectitude and

austerity on poor nations around the world. Countries that had crippling debt,

and no option but to ask the for a bailout, were saddled with an enforced

program of austerity – savage cuts to government budgets, evisceration of

welfare and other services, deregulation, wage reductions and widespread

unemployment. Credit should be encouraged for the private sector but severely

restricted for the public sector. This was supposed to bring struggling nations

back to financial sustainability – and, most importantly, to pay their debts to

the Wall Street banks and others who had made such imprudent loans in search of

a quick buck.

This was part of a hardline liberal program which became

known as the Washington Consensus. Its reflected assumptions that had not

materially changed since Adam Smith in the 18th century: that

governments should get out of the way and let markets do their magic. The fact

that it had invariably failed, and had condemned hundreds of millions of people

to penury while enriching a very few, did not signify.

Between the wars Maynard Keynes had rigorously opposed a

similar nostrum then rampant in Britain, where it was known as the Treasury

View. Instead of punitive restrictions being forced on debtor countries, he

usually favoured debt forgiveness and restructuring. Keynes died in 1946 but he

would have been a powerful voice against the fervent economic sages in

Washington. But that would not have suited Wall Street.

America and most western democracies embraced the hardline

approach and applied its formulas to their own economies. The result that

Keynes would have predicted played out over the next fifty years, culminating

in the Global Financial Crisis of 2007.

All of this raises a basic question: who are governments and

economies being run for? Is it government of the people, by the people, and for

the people – or something else?

An illustration of why it’s something else can be found in

the amount of public money the United States puts into military spending.

“This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a

large arms industry is new in the American experience,” he said. “The total

influence – economic, political, even spiritual – is felt in every city, every

Statehouse, every office of the Federal government …

“In the councils of government, we must guard against the

acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the

military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced

power exists and will persist.”

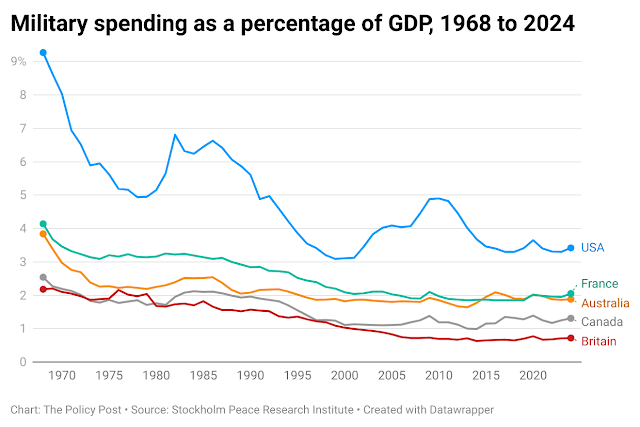

Even though America is not currently at war and has no credible threat to its integrity, 31% more (in real terms) is being spent on defence than in 1968, at the height of the Vietnam war. Spending reached a previous high just when the Cold War was winding down. There was an all-time peak in 2010, when the war in Afghanistan was still going but when the Iraq war was coming to an end. After the last American troops were pulled out of Afghanistan in 2021, the defence appropriation continued to increase. By 2024 it had risen to $US968 billion, or $2,900 for every resident of the United States.

This pattern of spending was reflected in Britain and

France. Australia is spending three times as much on defence, in

inflation-adjusted terms, as at the height of its involvement in Vietnam: $US33

billion ($A49.5 billion). That’s $A1,800 for every Australian resident. The

federal budget forecasts the defence bill will rise by 18.9% within four years.

The reason is that military equipment has become so

expensive. The numbers of service personnel have fallen but the hardware is

ever more complex. That, these days, is where the money goes: machines, not

people.

Perhaps it doesn’t matter after all. Although military costs

have gone up, economic growth has gone up faster. As a percentage of GDP, it

has fallen in the US from 9.3% in 1968 to 3.4% today. Australia has gone from

3.8% to 1.9%.

But there are many other demands on government budgets:

welfare, health and education. Those costs have risen too. And, despite all

that money being put into military hardware, America (and Australia) have not

been on the winning side in any war since 1945. There have been five: two

(Korea and the First Gulf War) ended in draws and three (Vietnam, Afghanistan

and Iraq) were lost.

The vast expenditure on expensive kit has a dangerous

consequence: it feeds the delusion that America is invincible. And so wars

happen, people die, and still more money is spent.

So if all this sophisticated, lethal weaponry isn’t capable

of winning any wars, what is it for? Who is it for?

Take the F-35 fighter program, which America’s Government

Accounting Office says will end up costing over $US2 trillion. The GAO has

serious doubts about spending that much money on this aircraft.

“The Department of Defense currently has about 630 F-35s, plans to buy about 1,800 more, and intends to use them through 2088,” the GAO wrote in a recent assessment.

“DOD's projected costs to sustain the F-35 fleet keep

increasing—from $1.1 trillion in 2018 to $1.58 trillion in 2023. Yet DOD plans

to fly the F-35 less than originally estimated, partly because of reliability

issues with the aircraft. The F-35's ability to perform its mission has also

trended downward over the past five years.”

Each aircraft costs between $US80 million ($A120 million)

and $US100 million ($A150 million). Australia has 72 of them.

The F-35 is made by Lockheed Martin, a giant in military

aircraft based in Maryland, not far from Washington DC. According to its annual

report it had sales over the past three years of $US204 billion ($A307

billion). Almost all of that was spent either by the US government or by

American allies around the world. Of the world’s top 100 defence contractors in

2023, 48 were in the US. In that year alone, they made defence sales worth

$US330 billion ($A495 billion).

They’re good at making money. Not so good at winning wars.

A similar malaise affects the health system in America and,

to a much lesser extent, elsewhere.

An analysis by the Commonwealth Fund, an independent health

policy think-tank based in New York, found the US had the worst health outcomes

of any of the ten nations it studied. Australia, which has a higher life

expectancy than any European nation, came out on top.

Again, the same question: if all that money doesn’t benefit

patients, who does it benefit?

Again, the same answer: those who sell, not those who buy.

Healthcare is a huge business worldwide but nowhere compares

with the freewheeling USA. The greatest money-spinners in the American system

are not the big pharma companies but the outfits that provide services, not

goods: insurance, distribution, managing the interface between health provider

and client.

The pharmaceutical business is big, just not as big.

Estimated drug sales in the US market in 2024 were $US574.37 ($A815 billion)

and are projected to reach $US1 trillion by 2030, a compound annual growth rate

of 5.9%.

Access to healthcare in America depends on your wealth and

on the colour of your skin. This is the sharp end of neoliberal economics.

Throughout the developed world, GDP – a measure of the value

of goods and services produced – increased by an average of 3.2% a year over

the 39 years to 2007. But the trend line shows that growth was inferior during

the neoliberal period from 1980 than in the period before. Despite all the

problems of the 1970s, the old postwar system produced better economic growth.

But how much of this (somewhat depleted) growth is real, and

how much does it come from just shoving money around without producing anything

tangible?

The stated purpose of the financial sector is to be the

bridge between those with money to invest and those who can use it for

productive enterprises. But during the four decades from the start Reagan’s and

Thatcher’s ascendancy, that purpose has become subordinated to the ingenious,

unproductive and plain dangerous dominion of financial engineers.

The growth of derivatives – a bewildering array of financial

“products” that packaged real assets into new and artificial formulations to be

traded, sliced up and repackaged, and sold again, with the ticket being clipped

at every stage on the way through. It comprises a huge industry, making vast

profits and paying very high salaries, but that adds nothing at all to real, tangible

wealth – the goods and services that people use.

Because so much money is being made, it adds massively

to GDP without adding anything to real

wealth. According to the Bank of International Settlements, the notional value

of derivatives in 2022 exceeded $US600 trillion. That’s more than 27

times global GDP.

Martin Wolf, economics correspondent of the Financial

Times, sees this diversion as a significant threat. In his book The

Crisis of Democratic Capitalism, he writes: “Behind [financialisation] is

the idea that the economy is just a bundle of tradeable contracts … Little of

this explosion of financial balance sheets went into financing fresh

investment.”

A side-effect of the proliferation of derivatives is that they conceal underlying risk. Investors no longer knew what they were buying. Eventually, the music had to stop, and it did so with a bang in 2007. And so, when huge numbers of dodgy American mortgages were packaged and repackaged into “collateralised debt obligations”, an over-leveraged international property sector found itself suddenly insolvent. Banks still holding these dodgy CDOs went to the wall, the financial system stopped working and the Global Financial Crisis ensued.

|

| The Lehman Brothers collapse: only the bosses prospered |

It was, yet again, proof that liberal free-market economics

does not work. Critical regulation had been abandoned in the name of an

ideology.

“The human toll was staggering,” notes the Investopedia

website. “According to data from the US Federal Reserve, by 2010, over 8.7

million American jobs had vanished. Nearly 10 million families lost their homes

to foreclosure. The average US household lost about $30,000 in home value and

$70,000 in stock wealth. The unemployment rate peaked at 10% in October 2009,

and many workers who lost jobs during this period never fully recovered their

earning potential.”

Even that was not the worst. Unemployment reached even

higher levels in Ireland and Portugal (both 15.5%), Spain (26.1%) and Greece

(27.7%).

The crisis saw massive bankruptcies and huge losses to the

life-savings of individuals around the world. Confidence and trust in financial

institutions and governments was shattered.

But the band played on.

NEXT: 7: The post-liberal malaise. With the Global Financial Crisis, liberalism had run its course. America is no longer the 'indispensable nation'. Other countries mist now find their own way.

.png)